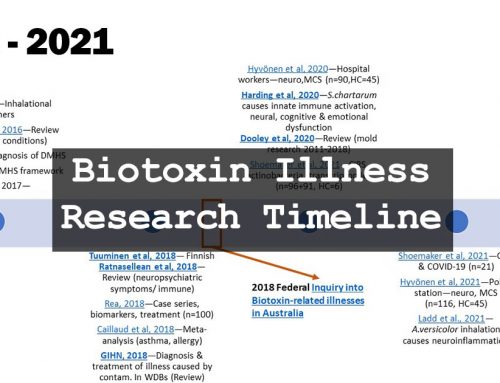

In 2018, the Australian Government conducted an inquiry into “biotoxin-related illnesses”—specifically, a little-known inflammatory disorder caused by exposure to certain microbes and their biotoxins in water-damaged buildings, such as some moulds. For those genetically susceptible ‘mouldies’ affected by Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS), watching as governments move heaven and earth for one epidemic while their own is belittled and ignored evokes mixed feelings. However, Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recently announced a targeted call for further research into biotoxin illnesses, bringing much-needed validation to this patient community.

Sean Di Lizio writes of his own battle with CIRS.

To discover that invisible microbial agents and their primaeval defence mechanisms have dictated much of your identity might just be to discover the secret of life. There is a dawning realisation that many of those personal struggles with anxiety and depression—which you were taught to psychologise and process—they were not yours as you thought. They were, rather, impersonal struggles—these mood disorders caused by microbes you previously never gave a second thought to inflaming your neuroimmune system. That your free will as you previously imagined it must be reconciled with a new reality concerning your environment: You are unmade by damp locations and inclement weather. Even that your naïve hopes and dreams, which you tried to follow for so many years, stood little chance against this microscopic foe. And if you start unravelling that thread, where does it end?

This paradigm change extends further than CIRS and relates to other forms of air pollution, toxic exposures, and who-knows-what-else causing neuroinflammation and an epidemic of mood disorders in our society: that depression and anxiety are often not endogenous. The science keeps reminding us that many of these mood disorders are warning us that our nest has been fouled and we are in danger; the urge to be anywhere but here when that system activates strongly is an ancient evolutionary instinct directing the organism to a safer environment. Moreover, it’s a warning that our brains might be in peril. But our civilisation is yet to absorb these lessons or their tremendous implications.

But stories must be personal in this culture of the self. So, here is mine:

At age six on Easter Saturday in 1988, my family and some friends sat down to dinner to eat a Coral Trout—a reef fish common enough around the Great Barrier Reef off the Eastern coast of Australia. We fell ill afterwards, my mother and I worse by far. I remember waking in the night completely paralysed except for my eyes. A chocolate Easter Bunny stood at the end of my bed, but I could not reach for it or move at all—quite the torment for a young child. We were diagnosed the next day with Ciguatera poisoning, the offending ciguatoxin having bioaccumulated up the ocean food chain all the way from a brown macroalgae—a dinoflagellate. While the others recovered quickly, my mother and I would have symptoms for many months. Over thirty years later, this would prove a clue in discovering that I possessed the genetic susceptibility to biotoxins associated with CIRS.

In January 2011, following the floods in and around Brisbane, Australia, I volunteered in the clean-up of water-damaged houses in one of the worst-hit suburbs. I remember one house that had been nearly submerged except for a distinct section of chimney, now reminiscent of a snorkel. This adventure in altruism took place without masks, gloves, or other forms of personal protective equipment. But from that day onwards, I suffered a number of related symptoms, including chronic insomnia, that no doctor seemed able to diagnose or understand. They offered prescription drugs to manage the symptoms, but the underlying cause was never identified. I wondered: Had there been something in the receding flood water?

Yes, the water was key, but the problem was in the air.

In March 2019, a contractor on our roof accidentally cracked and knocked off several roof tiles. The next time it rained, water dripped all throughout our kitchen and elsewhere, and the kids gleefully ran around with pots and pans and cups trying to collect it. This moment of levity served as harbinger for the worst year of my life. It would be less than a week later when my low-grade symptoms evolved into a full-blown case of CIRS, including a migraine that lasted four relentless weeks, was worse in the mornings and afternoons when I was at home, and seemed only to relieve slightly with time spent away from the house.

Despite a growing number of symptoms—over twenty-five at one point, including many physical such as blood noses and a tremor so severe I could no longer handwrite—no doctor seemed able to find anything wrong with me. For several months, I could not sleep for more than two or three hours each night, and few sleeping drugs had much effect. I told one doctor that I could neither recall any memories of my children from the past eight years nor any of the books I had read in the past three. Yet almost every standard blood test came back normal as did every scan. For a relatively healthy man in his late thirties who otherwise exercised, ate well, barely drank, never consumed illicit drugs, and even meditated, this experience proved frustrating and frightening. My entire life paused, placed on hold by a chronic illness with no diagnosis nor an end in sight. Worse, I began to be treated as if these severe physical symptoms were psychosomatic when I had never been sicker in my life.

Concerned for my problematic cognition, I read Dr Dale Bredesen’s The End of Alzheimer’s, in which he describes his research team identifying a subtype of Alzheimer’s Disease associated with Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS)—a controversial illness caused by microbial inflammagens (fungal and bacterial fragments) and their biotoxins (such as mycotoxins from certain moulds). I remembered that earlier roof leak and, from there, started asking for the right genetic tests, began finding the right doctors, and ordered the right blood tests that needed to be sent at great expense to the US. Suddenly, the tests all began pointing to the same underlying cause: This was environmental. I also reached out through my university for answers, where a professor of immunology explained to me that, regardless of the contested aetiology, my bloodwork would explain many of the symptoms I described and would also be expected to cause rapid cognitive decline. So, I started the first stage of treatment with binders such as cholestyramine to help remove the biotoxins from my body. We moved out of our problematic home, one so shady and buried in the ground that it would never be a healthy place for us. Briefly, I camped in the Australian Outback under cloudless skies where every day was dust-dry and 40-plus degrees Celsius—the drought, my friend and healer. Eventually, we remediated our old house of its mould and dampness problem before renovating and selling it, and could never imagine not living somewhere airy, light, open, and with a good roof.

And, after years of mysterious symptoms, my recovery began.

As a PhD candidate in an unrelated field, I began reading the relevant scientific papers and discovered the long history of biotoxin- and mould-related illnesses, hundreds of peer-reviewed studies, along with the sordid story of scientific misconduct by corporate and special interests in muddying the waters on this topic in order to avoid insurance and workers’ compensation claims and other forms of litigation. I learnt how a doctor who had previously worked for Philip Morris as late as 1997 to discredit the link between smoking and cancer, and with no relevant experience in this field, began publishing studies and reviews to discredit the burgeoning science that exposure to water-damaged buildings could cause health issues as severe as brain damage. That right-wing thinktanks and questionable lobbying groups are still conducting an ongoing disinformation campaign to this day to discredit this illness, just as was done with radium, coal, asbestos, and tobacco—and all for the same reason: money.

I learnt that it’s still an open-ended question as to whether this is a new or an old illness. Was it our extensive use of fungicides that evolved some of these common moulds and other microbial agents and made them more dangerous? Is this the fungal equivalent of antibiotic-resistant bacteria? And I also discovered an entire community of “mould avoiders”—as well as those fighting on the scientific and legal fronts to correct the record—and found solidarity. Now, I converse with CIRS-trained doctors and brilliant researchers in fields with brain-bending names such as psychoneuroimmunology, trying to better understand the role of dampness, mould, and biotoxins in human health, while working to communicate that to a broader audience. Given how my young daughter was also affected, albeit to a far lesser extent than me, you might well imagine how motivated I am to bring attention to this and other environmental illnesses.

But I have so far left out the dirty reality of this nightmare—the emotional hell-storm and attacks on so-many levels that must be endured: the brutal neuroinflammation, abnormal hormones, and associated depression and anhedonia; the neurological damage and loss of precious memories; the psychological trauma of bizarre lapses in cognition leading to sheer terror at being told I was on a pathway to early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease; the primal fear of never getting better; the medical circus, misdiagnoses, and mistreatment by some in the healthcare system; the months of isolation, sleeplessness, and exhaustion; the loss of home, contaminated possessions, and income; the betrayal by real-estate agents and insurance companies; and the abandonment, even bemusement, by sceptical friends, family members, and acquaintances, because your government is reluctant to formally acknowledge an illness that has such negative economic implications (even after one of their own, a Federal MP for the Liberal Party, the Hon. Lucy Wicks, fell sick with CIRS). It is true that this illness is poorly understood, but it is also true that the World Health Organisation acknowledged such health outcomes from dampness and mould had been noted in the literature back in 2009.

During those months of torture by sleep deprivation, the tired days would pass into long nights reacting to the bedsheets and my own sweat, hoping desperately each night to fall asleep. Hoping desperately that when I did, I would never wake. Or, at 3am, to finally begin drifting off, only for another vicious muscle twitch to jerk me awake, the result, perhaps, from damage to the motor cortex of my brain. More than just the bed—the couch, the car, and even my room at the university could all cloud my brain, irritate my skin, and cause the tremor and heart palpitations to resurface. These microbes obliviously bully you, shove you down with another exposure, and you shower, change your clothes, medicate, and try again, knowing you’ll only be pushed into the dirt again tomorrow.

Even one of my medications, among an impoverishing multitude of drugs and supplements, further affected my mood in demented ways. That in the fear and fog of just trying to be heard, under the spell of a desperation I have never known before or since, I lashed out verbally at some of my loved ones and am still making amends. Persecution came even after the correct diagnosis and a measure of recovery, only to have a psychiatrist walk into the hospital waiting room without even a hello and jovially say, “The good news is your illness isn’t real!” I felt afraid to tell many of my friends of my CIRS diagnosis following this and related experiences, nor did I possess the energy or composure to endure anymore such battles. There was also a deep shame concerning my brain damage—whether I wouldn’t be listened to or would be treated as less, which is exactly how some did treat me. So, to some friends who were once in my life, I have simply disappeared for much of the past two years.

Even one of my medications, among an impoverishing multitude of drugs and supplements, further affected my mood in demented ways. That in the fear and fog of just trying to be heard, under the spell of a desperation I have never known before or since, I lashed out verbally at some of my loved ones and am still making amends. Persecution came even after the correct diagnosis and a measure of recovery, only to have a psychiatrist walk into the hospital waiting room without even a hello and jovially say, “The good news is your illness isn’t real!” I felt afraid to tell many of my friends of my CIRS diagnosis following this and related experiences, nor did I possess the energy or composure to endure anymore such battles. There was also a deep shame concerning my brain damage—whether I wouldn’t be listened to or would be treated as less, which is exactly how some did treat me. So, to some friends who were once in my life, I have simply disappeared for much of the past two years.

It is not simply enough to say that I wished to die—more that this organism felt compelled toward literal self-destruction by some deep evolutionary impulse in order to end an unrelenting misery. In every alternate timeline to this one, I am certain that I threw myself from the twenty-fourth floor of the apartment building that I convalesced in. That I can tell you what the fresh air felt like on my face as I stood on the balcony and how nothing else restrained me other than the thought of two small children.

This tale also excludes the rising horror inherent within so many lesser memories as a long-standing puzzle is solved and the narrative of a life and an identity is unwritten: the water-damaged, mould-spotted book that made you and only you sick; that holiday apartment in Queenstown, New Zealand, which made you anxious and paranoid until you left; the heart palpitations and panic attacks when you visited that certain cinema; a pattern of mental-health struggles that matched the pattern of water-damaged houses you lived in as an adult. All is compounded upon realising that so much past misery, both mine and even some inflicted upon others, was unnecessary—amplified by this illness. And while the worst effects of this illness might have come after that roof leak, I possess little doubt that the mood disorders and increasing acalculia that followed my time living in a sub-basement in my early twenties contributed to the slow demise of my first career as an engineer.

Could anyone ever unpick such a wretched knot of confounding factors and know the precise truth? I certainly never will. The outcome would be the same regardless: This crazy-making illness broke me. All human pretence was lost, and what was left was an animal crying, sobbing on the tiles beneath the showerhead, bereft of all grace, while the water washed away all denial and delusion. For more severe cases such as mine, or those not correctly diagnosed for years upon years, many CIRS-trained doctors consider this illness deeply traumatic: Your body and brain are affected, your life, career, and friendships, even your own history and identity, your material possessions and wealth, while wondering if you’ll ever find a healthy location, and all while battling an often hostile, often dismissive medical system. But all of that pales at the insidiousness of an illness that seems to target and destroy every mechanism the brain has for creating love and joy and purpose, leaving you gasping at the absence of a psychological air you had never before noticed you were breathing.

In case anyone claims I exaggerate or indulge in too much self-pity: I recall patients in a support group comparing their mould illness with other ailments they had endured. For a soldier wounded with broken bones and burns over two-thirds of his body? Mould was worse. Lung cancer with part of their lung removed plus over a metre of their bowel and a major tachycardia event during the operation? Mould was worse. Scalp ripped off, five fractures in their spine, and severe vertigo for two years following a car crash? Mould still won. Traumatic brain injury, skull fracture, and even a brain haemorrhage? That was described as desirable compared to the thought of enduring CIRS again.

Few friends will ever—could ever—understand this journey fully, although a few might eventually be surprised to realise their own struggles are related. And that just making my peace with the price I’ve paid in every aspect of my life has been as herculean an ordeal as the illness itself.

Despite all of this, we are the fortunate ones. Yes, truly. We found the correct diagnosis, could afford to move home and access proper treatment, and our family was not ripped apart by either ill health, financial strain, divorce, or even suicide. My incredible wife somehow held our family together through all of this when I was physically present but otherwise absent—lost to a traumatised and disordered mind. And several friends and family members were incredibly understanding, a few displaying a compassion and quiet empathy that I can only envy. What is more, my daughter and I responded well to the few treatments that are known for this under-recognised illness. Somehow, I wound up at the cutting edge of medicine and even have volumetric MRIs of my brain showing the reversal of neurological atrophy—a feat only considered possible in the peer-reviewed scientific literature since 2014, and a feat still only possible if we catch that atrophy early before it becomes too advanced.

Moreover, Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council recently published a consultation paper on biotoxin-related illnesses and pointed out there is a “growing body of evidence in this area.” The past decade of studies keeps showing that we are not crazy to be talking about chronic fatigue, headaches, fibromyalgia-like pain, vision problems, gastrointestinal tract issues, along with severe cognitive symptoms, and that one in every ten Australians occupies unhealthy housing likely to adversely impact their health. It is a hidden epidemic and one this country cannot even uncover right now, because we lack any pathologies that can accurately test all of the necessary biomarkers. Perhaps most frightening of all are the preliminary studies concerning the detrimental effects on the development of children.

I will never precisely know the long-term effects on my own children. It still bothers me. But despite the immense consequences of all that passed before, I can now live with clear thoughts, a sharp decrease in obsessiveness, no depression, and an unfamiliarly disturbing lack of anxiety. That provided I avoid living or working in the wrong environments for too long, neuroticism need not be my constant friend. With fifteen years of both PTSD and CIRS ended, I have become a stranger unto myself. Now, the slow days and small moments once again bring their own quiet joy. And while I still bear some mental scars, I am back to being a caring father and loving husband.

Is this some storybook moment to tell you of the lessons learnt or how the hero triumphed? No, certainly not. All I know is that, for the first time in a long time, I am simply grateful to still be here. But stories that end as happily as ours are too rare where CIRS and related syndromes are concerned.

The blame for that is not to be laid at the feet of those doctors who were misinformed on this niche of medical history. Nevertheless, it is time to pass our good fortune forward—to educate, to enlighten, and to ensure that help is given where help is possible. There are still so many others yet to be diagnosed, who don’t even know that they are just waiting for their lives to be returned to them.

Sean has previously moderated the Toxic Mould Support Australia Facebook group in order to support other patients with this illness. He was the lead author of CIRS Explained, a primer on the history, research, diagnostic process, treatment protocols, and controversy of CIRS / mould illness. As well, he contributed significantly to the Science Primer and Biotoxin Research Database. He and his family were featured on Australian television program The Feed (SBS), in June 2021, talking about his CIRS journey. With Macquarie University’s Professor Gilles Guillemin, he helped to write a grant application that won funding from Australia’s NHMRC for further research into CIRS. As part of this grant, he is currently coordinating a team of academics writing a literature review on this topic.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.